The Zen rebels: obscure hermits and existential reformers (part 16) Yokoyama Sodō

Our humility, as a human being whether male or female. Is the intrinsic focus of returning to what the Buddhist call the original mind or Buddha Nature, the Zen see this as being aware that nothing is permanent, everything cycles back into nothingness, ending within the void. The beginning and end as simultaneous points in time. To know this, is not embracing the fatalism of nothingness, but understanding impermanence. To not be attached to this world. Attachment to the temporary leads onto suffering and in its pure form of detachment, Zen explains to the practitioner; to leave is also returning to its original place. To neither be attached or detached from self and what we deem as the materialistic. All perish in time. To live fully in the moment is to understand Nirvana within the now, yet to embrace the simplicity of life. To value it, to be humbled and to know what its is to just live. We we look down through the ages of the Zen monks, masters, the rebels, iconoclasts and reformers – and it is there hermitage which is the most admiring. That when viewed it is seen to be the pinnacle of separation of burden, that is the material world and suffering. Yet, they do not judge or preach. To live alone, separated yet connected to the natural world. Is paying respect to founder of Zen and Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma, who, if myth is correct meditated in a cave for 9 years. He broke that human bond of attachment to nature and the nature of the self, whilst cultivating what the Zen Buddhist deem as the true nature – of being of nothing and by its definition becoming everything.

But, also in saying that. To be humble is a quality that one can attain without any religions instruction or mysticism. Is to know that at some point, maybe due to misfortune, one must return to zero. Within the material world, to live simply, to build within a day and be grateful for those moments. From lofty heights to the lowest levels. One must know all aspects are the same. You retain the body and mind, but once again they will be temporarily. It is enough just to breath and live.

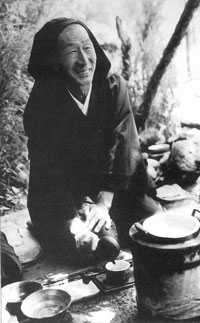

Yokoyama Sodō was born 1907 in Sendai, Japan. As a young man, he was attracted to Sōtō Zen, residing at the Antai-ji temple for eight years between 1949 to 1957 as he sought the guidance and teachings of the enigmatic Sōtō master Sawaki Kôdô Roshi. After being granted the title of Roshi, Yokoyama then left Antai-ji and moved to a nearby park in Komoro City. This is where he started to become this very unique 20th Century Zen hermit in what he would call his “temple under the sky.” In comparison to his old master Sawaki, who was a very characteristic character, he gave talks and had many followers outside from the traditional Zen setting. On the other hand, as his former pupil Yokoyama which could be easy labeled a 'loner', when he decided to take what he learned as a Zen monk and embrace that mastery of the solitude Zen Master. Residing in Komoro park from 1959 to his death in 1980. And all he needed where he sat underneath the foliage of the park trees was a self-constructed plastic canopy, a small stove, a rustic teapot, pan, cup and a bowl. But, not to be idle in his discipline, Yokoyama's Zen was humbly to be shown to the public, as a visible and audible presence to the people and tourists who visited the park. A modern day Zen hermit, also embraced the flair of his humble appeal. Utilizing brushes, paper, ink sticks and an ink block. Yokoyama would write his poetry, selling it to the passersby. Enticing them as a solitary Zen master, he would use the leaves that surrounded him as a flute, by taking each one between his fingers and blowing – he was able to create various notes and tunes, he was later known as Kusabue Zenji (Zen master with the grassflute).

"What a strange thing this zazen is. When we practice it, distracting ideas, irrelevant thoughts — in short, delusions, which ordinary people are made of, suddenly seem to feel an irresistible temptation to arise and appear on the surface. Then there is a desire to drive these thoughts away, in irresistible desire to which our complete effort is added. Those who don't do zazen know nothing about this. Why is it that when we practice, deluded thoughts continue to surface one after the other? The reason, which we learn from Zazen, is that each one of us, from prince to beggar, is an ordinary (deluded) person. The attempt to drive these deluded thoughts away — delusion being so much nonsense (interfering with the happiness of oneself and others) — is also something brought home to us through zazen. We tentatively call this zazen that guides us in this way, 'Buddha'."

Yokoyama Sodō

Comments

Post a Comment