The Zen rebels: obscure hermits and existential reformers (part 10). Ikkyū Sōjun (part 1)

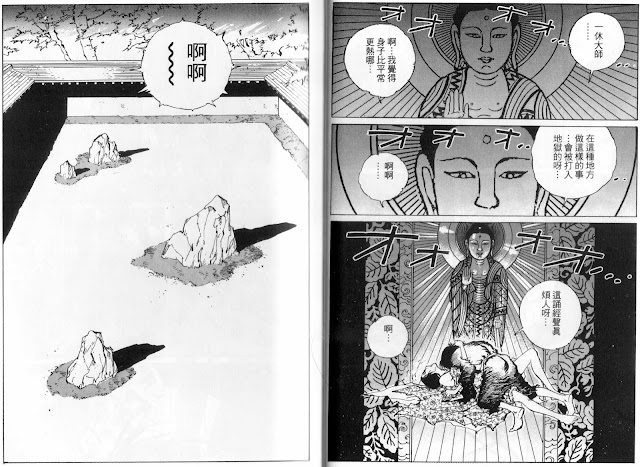

(Image from the Hisashi Sakaguchi 1996 comic "Ikkyu")

“Anybody can enter Buddha's world, so few can step into the Devil's” Ikkyū Sōjun

For me personally, it is Ikkyū Sōjun who lived through Japan's tumultuous period (Sengoku) of the 15th century, as a maverick Japanese Zen Master, poet and probably one of the most iconoclastic proponents of Zen in history, who outlines, through his poems and personae, something deeper. That we are all human, extraordinary flawed with our pain and suffering. The contradictions of desires and the ridding oneself of the burdens of life and death. Can and from Ikkyū 's perspective lead to more suffering. Ikkyū, despite his training as a Rinzai Zen monk, personified the troubled mind, as he lay witnesses though his wanderings, the suffering onto others and of ourselves. To what is, in most cases, self imposed, that in so many ways under Zen should be seen as necessity to know. To learn from it, to endure, but as the late American author Charles Bukowski once said, “...maybe not to endure.” As we look at the poems and life of Ikkyū, we may never really find the truth, the meaning of life. Or even the Buddha nature from within, to what Zen teaches is within all of us, yet, to which Ikkyū does emanate the Buddhist perspective that we are within a karmic cycle of birth and death, rather, paradoxically for Ikkyū there is only an inherent conclusion to life and death. It ends. That is death as a fervent realization of what life is, should be enjoyed. Lived. Ikkyū, maintaining the Zen philosophy that life and death are as a single entity within existence – he also prescribes it as one day, however it is spent, is to see it for what it is. There is nothing else.

And this alone, when confronted with the self is a frightening disposition, which neutralizes the euphoria and recklessness of seeing life as an infinitum. A planned template, that Ikkyū saw as a flawed and ruinous way to be, aware of the anguish that it creates in anticipation of a future. When the planned idea of a future day is removed, life becomes more sacred. And it is these simple aspects of life, devoid of the trivialities, which Ikkyū viewed when he was a young monk and his decision to become a vagabond, was the distraction that people used against their fears of death. And yet, it was these trivialities and fears that lead to the perpetuation of death and destruction. Which he saw were mostly inflicted onto the peasants, farmers and fishermen, who suffered under tsunamis, famines, wars and attacked by bandits. With the hierarchy of feudal Japan having very little interest or care of their existence. So, Ikkyū admired the simplicity of the peasants, who lived more closely under the spectra of death. Songs of the fishermen, the drinking of sake and the eating of sushi. The brothels and the sex. Which is all they had. And for Ikkyū, through is own fraught mind, he embraced completely. He was no martyr or savior, but rather a Zen Master, who through his poetry. Realized that life, to understand is to know that it has no immediate purpose, beyond all of its bliss and pain. For Ikkyū it is to live entirely.

"With a young beauty, sporting in deep love play; We sit in the pavilion, a pleasure girl and this Zen monk. Enraptured by hugs and kisses. I certainly don’t feel as if I am burning in hell."

“Follow the rule of celibacy blindly, and you are no more than an ass; Break it and you are only human. The spirit of Zen is manifest in ways countless as the sands of the Ganges. Every newborn is the fruit of the conjugal bond. For how many aeons have secret blossoms been budding and fading?” Ikkyū Sōjun

___

Authored by Adrian Glass (2018)

Comments

Post a Comment